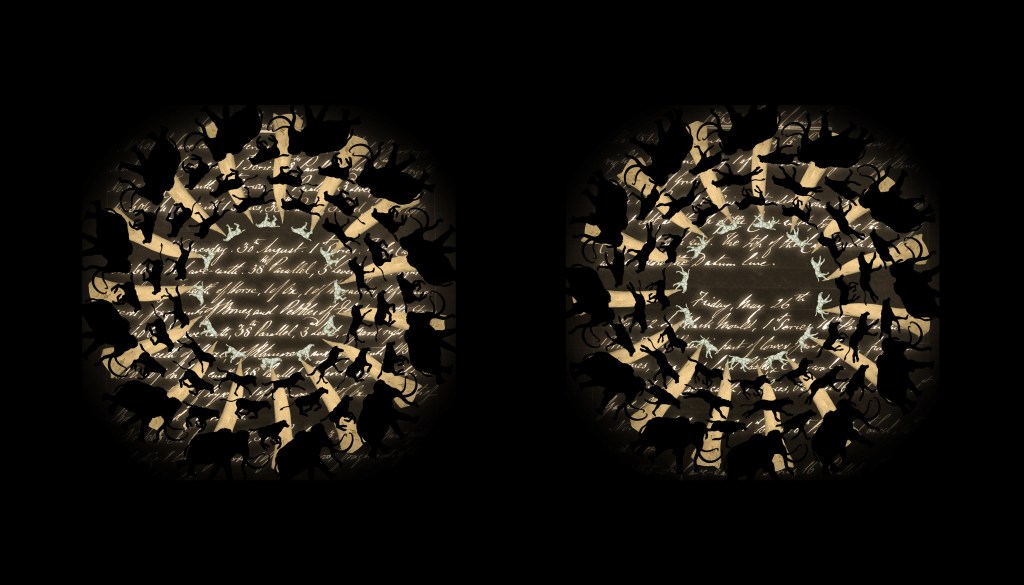

Pages from William Pengelly’s journal from the excavation of Kents Cavern and bone awl (Torquay Museum). Paper cut-out mammoth, cave lion, wild horse and Homotherium by Sean Harris

William Pengelly was a Cornishman, the son of a sea captain who left school at the age of twelve to join his father’s crew. He was shipwrecked once and saved from drowning twice before being brought back to Looe on the death of his younger brother in an accident. Here, he set about teaching himself mathematics before becoming a private tutor.

Perhaps these early experiences gave him a different perspective to the Oxford Men, Buckland, Lyell, Dawkins and all. And maybe it was this that enabled him to navigate the distinctly choppy political waters surrounding the excavation at Windmill Hill Cave, Brixham, which was to play such a significant role in establishing the so-called ‘Antiquity of Man’. Correspondence suggests the Committee to be a wriggling mass of egos and untruths as the men of science each sought to claim credit for the important discoveries being made. In all this subterfuge, the name of Falconer – who had cast doubt on the provenance of MacEnery’s ‘bear’ teeth – particularly stands out.

The teeth themselves had, over the course of three decades, been the subject of a debate almost as fierce as the predator from whose formidable dentition they hailed. In this time, it had been reclassified, ceasing to be a bear (Ursus cultridens) and becoming Machairodus latidens; something like a cat. Indeed, as early as 1826 Buckland had written of them as being from

‘an unknown carnivorous animal, at least as large as a tiger; the genus of which has not yet been determined.’

Pengelly, like MacEnery before him, seems to have been deeply wedded to Kents Cavern – possibly a reflection of his West Country roots. Perhaps because of this, he seems to have supported MacEnery where Buckland, Falconer and the others had cast doubt on his work – which, we should remember, had yielded solid evidence of the ‘Antiquity of Man’ four decades before the excavation at Windmill Hill. And within the story of the ‘Cave Hunters’, as these Victorian gentlemen became known, the Machairodus of Kent’s Hole seems to have become the conflicted avatar of truth – or untruth – in carnivorous, nearly feline, form.

Following in MacEnery’s footsteps, Pengelly set about the excavation of Kents Cavern in 1864 using the same meticulous techniques that he had evolved for Windmill Hill Cave. He later wrote;

‘in 1858, the results of the systematic and careful exploration of Brixham Cavern, on the opposite shore of Torbay, induced the scientific world to suspect that the alleged discoveries which, from time to time during a quarter of a century, had been reported from Kent’s Hole, might, after all, be entitled to a place amongst the verities of science’.

But along with the ‘verities of science’ the Machairodus also appears to have occupied his thoughts:

In his excavation report for the earlier part of 1871 he laments;

‘The Branch of the Cavern termed the Wolf’s Den by MacEnery, and in which he found the celebrated five fine canines of Machairodus is immediately on the right, or north, of our present work but we still have to state that we have met with no trace of that huge Cave mammal.’

And then later that year;

We commenced the exploration of the Wolf’s Den on July the 12th 1871, and from time to time we cherished hope that we might, like MacEnery, find in it some traces of Machairodus.

But on the 29th July, 1872, after eight seasons of digging Pengelly finally – yet with no apparent rush of emotion – records;

No. 5962. In Cave-Earth, 4th parallel, 1st Level, 1 yard right, including 1 tooth in left lower jaw of Bear and 1 of Machairodus.

At last! What a moment when the candle illuminated the distinctive serrated edge after eight years of painstaking digging. And what a contrast in surveying and recording methods to Dawkins’ hastily scribbled notes from the Hyaena Den…

Pengelly’s work at Kent’s Cavern was to continue with the same rigour and mathematical detail for a further eight years. By the time of its conclusion MacEnery’s work had been thoroughly vindicated – nearly forty years after his death.

And like William Beard at Banwell earlier in the century, Pengelly records a steady trickle of dignitaries – amongst them the nobility of Europe including members of the British, Dutch and Russian royal families and even Napoleon III – making pilgrimages to Torquay to inspect the discoveries that were profoundly altering the Victorian universal view.

Plainly, the work of the Cave Hunters still held a grip over society… and the scimitar-toothed one still had them in its clasp…