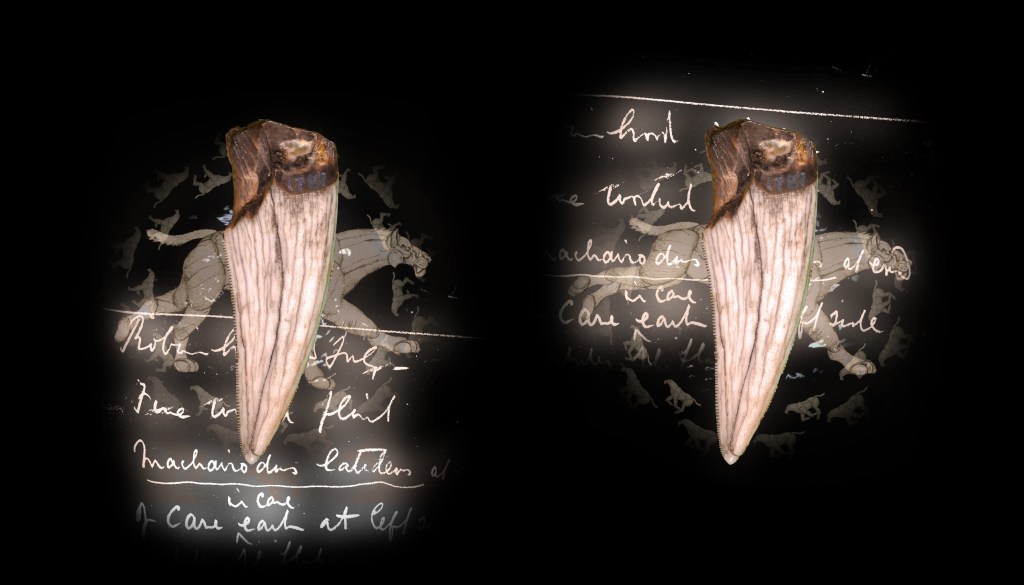

Canine tooth of Homotherium latidens and pages from William Boyd Dawkins’ notebook from the excavation of Robin Hood Cave, Creswell Crags (Manchester Museum). Paper cut-out Homotherium by Sean Harris

In 1873, Mr Frank Tebbet, supervisor at the Creswell Crags limestone quarry in Nottinghamshire found fossils in the mouth of Robin Hood Cave, one of a series of caves in the rock face of the spectacular gorge. As a result, in July 1875 the Reverend John Magens Mello, a graduate of St. John’s College, Oxford and Thomas Heath, the curator of Derby Museum and Art Gallery commenced excavations in the gorge. Heath, the son of a tile cutter, had left school aged twelve to take up an apprenticeship in the same profession as his father but abandoning it, had progressed to assume the curatorship of the museum by the time he was twenty five.

They quickly found not only the bones of horse, woolly rhinoceros, bison, hyaena, mammoth, elk and lion – but also stone tools.

By the following summer another familiar Oxford Man, William Boyd Dawkins, now curator of the Manchester Museum and a professor, had manoeuvred himself into the position of site palaeontologist. Along with Mello and Heath, Dawkins formed part of the Exploration Committee which was made up of preeminent (and entirely male) researchers in the field. As at Windmill Hill Cave, the committee appears to have been a hotbed of academic rivalries – and there was already considerable animosity between Dawkins and Heath. The excavations were not, however, conducted with the mathematical precision of Pengelly’s in Devon – perhaps, in fairness, because of the cost of doing so.

The 3rd of July 1876 saw a momentous discovery which would have far-reaching consequences. Heath recorded that ten minutes after Dawkins appeared at Robin Hood Cave for the first time that day;

‘when Mr Dawkins was chatting with my friend and me, the men laid bare a small escarpment, when we saw a canine, which Mr Dawkins immediately recognised and exclaimed “Hurrah! The Machairodus!”

Heath’s later testimony, also attributed to the workman Moses Hartley, extends Dawkins’ exclamation adding;

“Oh my! Pengelly will go wild when he hears of this! It will spread like wildfire over Europe!”

The beast had resurfaced once again.

The tooth, of Homotherium latidens, the Scimitar-toothed Cat was to provide the spark that ignited a very public and embittered war of words between Dawkins and Heath. For Heath harboured suspicions that Dawkins had planted it in the cave.

After remaining silent for three years, he called Dawkins out.

We can never know for sure the precise truth, which resides in two rival testimonies. But what is certain is that Dawkins proceeded to use the media of the day, his influence and his status to destroy Thomas Heath’s reputation. The battle between the two effectively became a soap opera played out in the national and international media.

Equally apparent is that Heath was meticulous in his work – and that his account of the circumstances surrounding the discovery raises a number of questions; not least surrounding how Dawkins, at a distance of nearly ten feet and by the light of two candles, was able to identify the tooth so precisely. Furthermore, both Heath and Moses Hartley had remained in the cave after Dawkins’ exit – and, having inspected the hole from which it had sprung, came to the conclusion that it had been made with a pick – into which the tooth had been dropped from above…

Dawkins, it has been suggested, had sought to engineer a story to rival Pengelly’s at Kent’s Cavern, effectively tampering with the science. And in doing so, he cast a shadow over his own reputation – which remains tarnished to this day.