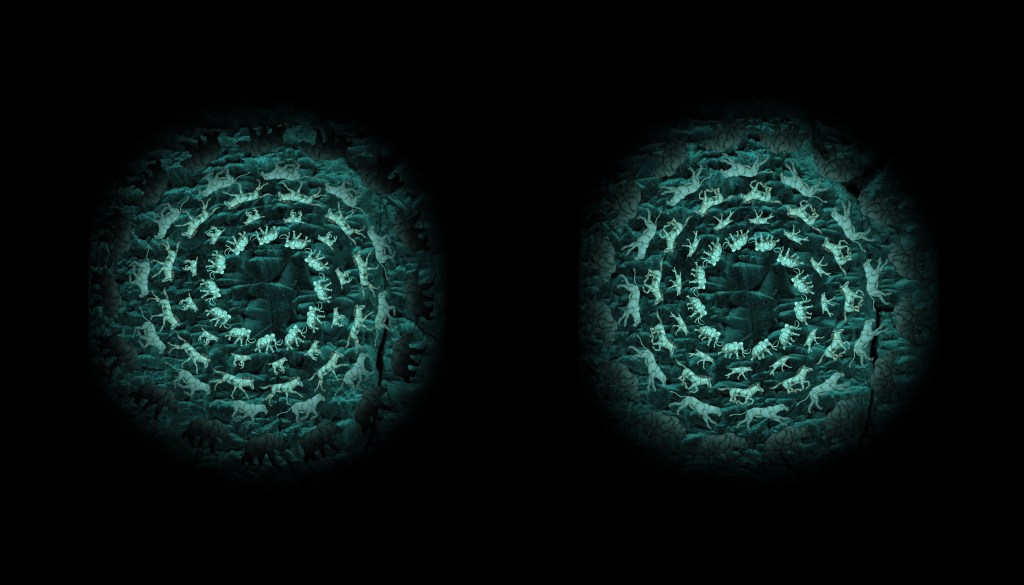

The Ark Tablet (British Museum). Paper cut-out cave bear, cave lion, wild horse, hyaena and mammoth by Sean Harris

Ten thousand years ago in the Near East – but at other times elsewhere – people learned to grow crops and corral herd animals. This meant they could stay in one location and didn’t have to carry everything around with them, so perhaps were better placed to create things from materials that were heavier and more permanent in form. As technologies evolved they began to write things down in more enduring formats so as to ‘fix’ them; literally setting them in stone.

Perhaps they thought – as we might – that this would make things clearer and less prone to dispute, although emails often demonstrate that this isn’t always the case. On the whole, they compiled lists that showed fairly boring but nonetheless important stuff relating to stocks, crops, ownership and that sort of thing. But they did occasionally write down stories as well – and one tablet of what is known as cuneiform writing has been translated as relating the familiar story of the Great Flood. It’s called the Ark Tablet and it was created nearly two thousand years before the time of Jesus.

Perhaps, as this time of a written truth emerged, the universe of memory held in myth and legend became increasingly submerged, along with the memory of great beasts once hunted and now banished to the edge of shadows. But the mortal remains of these creatures resurfaced occasionally to set the imagination spinning – particularly when they evoked sharp-toothed predators that might have feasted on us. And apparently this powerful magic remains today…

In some places, the memory held in stories stayed strong and is now being shown to tally with scientific research. This is true of Aboriginal flood stories in Australia which are thousands of years old. Such tales, in which many generations of knowledge are bound up, have been preserved because what they say is, for one reason or another, of great importance to those people. In Arnhem Land living stories of the Thylacine – the marsupial wolf – are still told two thousand years after its disappearance from that landscape. Maintaining the memory of the Thylacine as a component in the universal order is important to the people who live there because they recognize themselves as being part of that order. The Thylacine is part of who they are – as is its story.