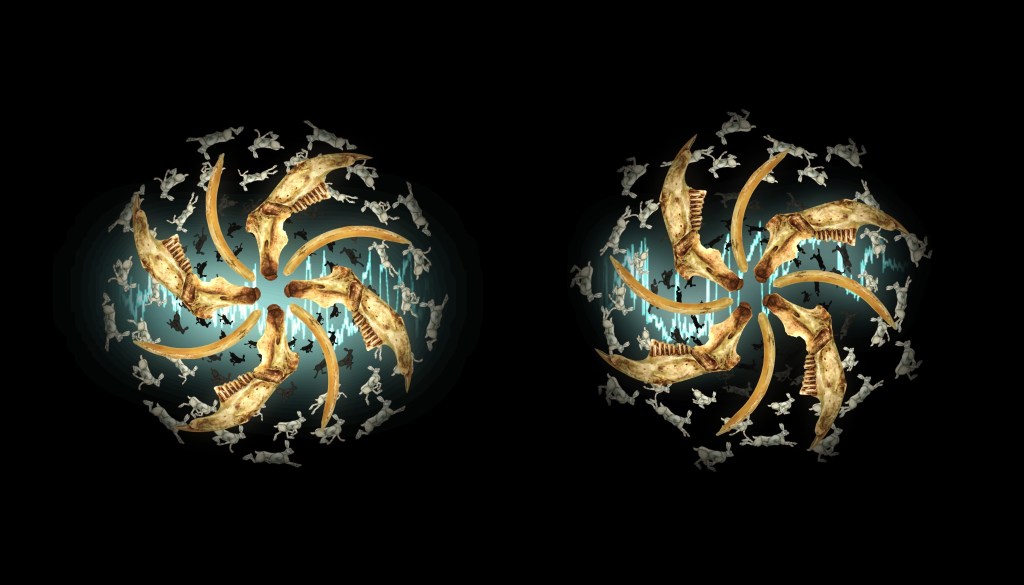

Narrow skulled vole mandible, rodent incisor and graph showing temperature fluctuation over a 50,000 year period (Professor Danielle Schreve, Royal Holloway University London). Paper cut-out mountain hare by Sean Harris

Danielle Schreve is today, Professor of Quaternary Science in the Department of Geography at Royal Holloway, University of London. The Quaternary Period is the last 2.6 million years and is divided into two epochs; the Pleistocene (2.58 million years ago to 11.7 thousand years ago) and the Holocene (11.7 million years ago to the present day).

Using a variety of processes available to modern science, she extracts information from ancient animal bones and interprets the data so as to understand the impacts of abrupt climate and environmental change on the fauna of the period. In this way, she can help to predict what the impacts of future climate change may be because many of these creatures – or at least their close relatives – are still with us. And thus we can gain an idea of what may happen to entire ecosystems and therefore – because we are a part of them – to us.

Her research draws and builds upon the scientific legacy of Dorothea Bate – and indeed the Cave Hunters of the nineteenth century going all the way back to William Buckland, who collectively deduced that our landscape had been inhabited by both cold and warm climate creatures at different times over many millennia. Science isn’t about one person or one fixed story. It’s a constantly unfurling and morphing narrative of twists and turns – which sometimes springs surprises as new discoveries are made.

Danielle has been excavating Gully Cave in the Mendip Hills in Somerset since 2006. Each year she and a team undertake a couple of weeks of meticulously planned digging using methods which both Buckland and Pengelly would recognise and endorse – though perhaps not Dawkins. Soil is removed and sieved with painstaking care, for as Dorothea Bate showed at Merlin’s Cave, tiny mammal bones have at least as much of a story to tell as those of the megafauna. Material is finally removed to the lab at Royal Holloway where analysis is undertaken for the rest of the year and beyond – bringing to bear new technologies that would astonish the antiquarians such as ancient DNA analysis, 3D visualisation and bone chemistry to reconstruct past diet and movements.

This research is steadily forming a high resolution picture of the changes that have taken place over the last 100,000 years; how species have come and gone as the climate has warmed and cooled. The reindeer for example, was present 11,500 years ago but no longer runs over the Mendip Hills because it’s now too warm there for a creature so perfectly adapted to the cold. They, as we know well, are solely creatures of the Arctic and Sub-Arctic – but how long before it becomes too warm for them there? When this comes to pass they will vanish. And perhaps we, who are dependent on healthy biodiversity for our own well-being, will follow, having first been forced to retreat to habitable refugia – as science shows our ancestors did before us.